Monday 24 December 2018

Peeing in 21 seconds

Do you know how long it takes you to empty your bladder? How about your cat, dog or horse? Do you reckon that the time will be more or less for the elephants at the zoo? Would it surprise you to learn that there is absolutely no difference?

It turns out that it takes 21 seconds for a healthy mammal – of any species – to empty a full bladder. As you might expect, an elephant has a much larger bladder than a mouse, but the mechanism for emptying it compensates so that the peeing time is exactly the same.

This amazing discovery was made by Patricia Yang, a mechanical engineer based at the Georgia Institute of Technology, and the research earned her an “Ig Nobel Prize” – this being an award given to scientists whose work is either absurd or bizarre. In this case, the “bizarre” label seems to be more appropriate, as it conjures up a vision of the lady in question going round her local zoo armed with a stopwatch and waiting for various animals to go to the loo.

Patricia Yang did not stop there. She also worked out that all animals that poop in cylindrical form - including humans – take twelve seconds to do so. Personally, it always takes me a lot longer because I take the newspaper with me to the smallest room!

© John Welford

Wednesday 19 December 2018

Animals make elements

Sunday 18 November 2018

The Oxebode, Gloucester

His head on the pathway, his feet in the drain.

The lane is so narrow, his back is so wide,

He got stuck in the road twixt a house on each side.

He was stuck just as fast as a nail in a crack.

And the people all shouted ‘So tightly he fits

We must kill him and carve him and move him in bits’.

Of his ribs and his sirloin, his rump and his tail.

And the farmer he told me ‘I’ll never again

Drive cattle to market down Oxbode Lane’.

© John Welford

Sunday 4 November 2018

Dilys Price: skydiver

Thursday 4 October 2018

One hour's TV was enough to start with

The Shaftesbury Byzant

Friday 21 September 2018

Could a giant squid sink a ship?

Wednesday 12 September 2018

Mr Lyle's crimconmeter

Monday 30 July 2018

Chinese thoughts on salt and blood pressure

It is well known that salt in the diet is a

major cause of high blood pressure, which in turn is a contributory factor in

strokes and heart disease. It therefore follows that reducing one’s salt intake

is a good idea.

In China this message has been conveyed by

teaching children in primary school about the dangers of salt, and they in turn

have passed this on to their parents and grandparents. The programme began in

14 schools, with follow-up monitoring of their immediate families. This found

that levels of blood pressure showed a marked decline, with daily salt intake

declining by a third of a teaspoon in children and half a teaspoon in adults.

It has been estimated that if this rate of

progress was replicated across the whole country, more than 150,000 deaths from

strokes and 47,000 from heart attacks could be prevented every year.

So could this method of getting kids to

preach the anti-salt message work in other countries? It sounds as though it

could be worth a try!

Tuesday 26 June 2018

A poisoned chalice?

Monday 25 June 2018

The dragon of Halong Bay

Wednesday 28 March 2018

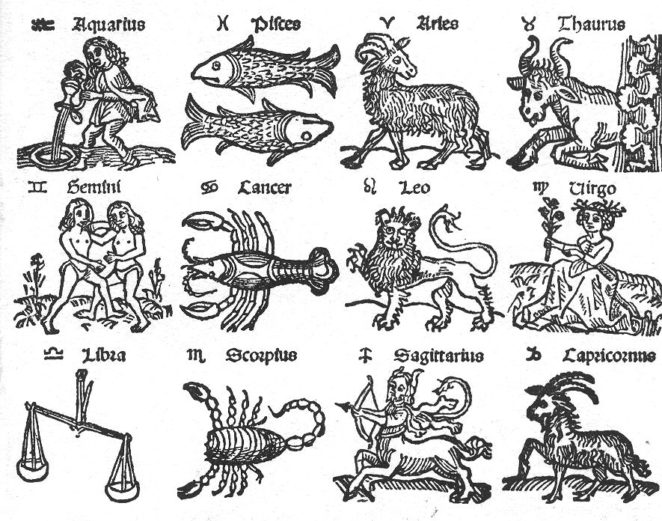

Zodiacal nonsense

Tuesday 27 March 2018

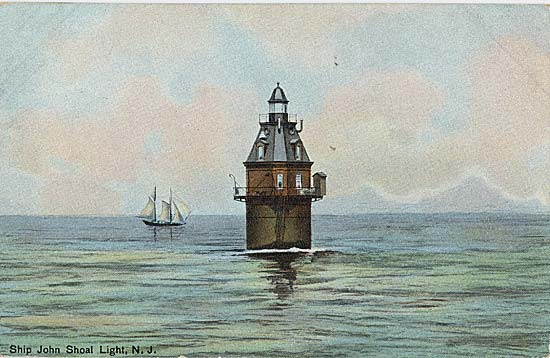

Two lighthouses - haunted or cursed

The Worm Charming World Championships

Monday 26 March 2018

The ring finger

The fourth finger (if the thumb counts as

the first!) is traditionally the finger on which engagement and wedding rings

are worn. But why is this?

It comes from an ancient (and entirely

erroneous) belief that a nerve runs from this finger directly to the heart.

Given that the heart has always been renowned as the seat of love – hence

“giving your heart” and having “heart-felt emotions” – the link to the rings

that signified love was appropriate enough.

This idea is also the reason why the finger

has been called the “medical finger”. The Greeks and Romans reckoned that the

nerve mentioned above would “warn the heart” if the finger came into contact

with anything noxious, so the finger was used to stir medical concoctions.

Presumably, if your heart jumped a beat during this process you would stop

stirring and re-constitute your mixture so that it would be less likely to kill

the patient!

Despite the complete lack of evidence for

this belief, some people still maintain the superstition that it is unlucky to

rub in ointment or scratch the skin with any finger other than the fourth.

© John Welford

Sunday 25 March 2018

The highest mountain is not the tallest

The ghost of Pawleys Island

Saturday 24 March 2018

The exception that proves the rule

Tuesday 20 March 2018

Not the Loch Ness Monster!

Saturday 17 March 2018

Don't fly your flag upside down!

Thursday 15 March 2018

Burning ears: an ancient superstition

The superstition – for it is nothing more than that – only applies when the talking is being done way out of earshot – it is not the case that you suspect that you are the subject of discussion between people on the other side of the room but can’t quite hear what they are saying.

It might surprise you to learn that this notion owes its existence to the Roman writer Pliny the Elder, who wrote during the first century AD and was a victim of the eruption of Vesuvius that buried Pompeii and Herculaneum in 79 AD. Pliny set out to write down as much knowledge – about everything – as he could gather, producing 37 volumes of his “Natural History”. It was his insatiable curiosity that prompted him to get too close to Vesuvius.

In Book 28 of Natural History Pliny wrote a collection of commonly held superstitions, and he managed to find and record around 20,000 of them. Somewhere on the list was:

“… it is believed that absent people divine, by the ringing in their ears, that people are talking about them.”

It is important to remember that Pliny’s intention was to debunk all these superstitions, not to publicize them, but the latter does appear to have been the end result.

One writer who took up the idea – whether directly or indirectly from Pliny is not known – was Geoffrey Chaucer, who used it in his Troilus and Criseyde, written in the 1370s. Criseyde’s uncle Pandarus tells her that he and Troilus will:

“… speak of thee somewhat … when thou art gone, to make thy ears glow”

This is not quite what Pliny had in mind, given that the person with glowing ears is not supposed to know that they are the topic of conversation, but only to assume that they are - due to the red ears!

Although this is clearly a piece of nonsense, as Pliny tried to make clear, the superstition is still around nearly 2,000 years later. However, let’s hope that not too many people take it seriously. It is almost always mentioned as a joke, such as: “We were talking about you yesterday, were your ears burning?” – to which the answer should always be “No”!