Wednesday 28 March 2018

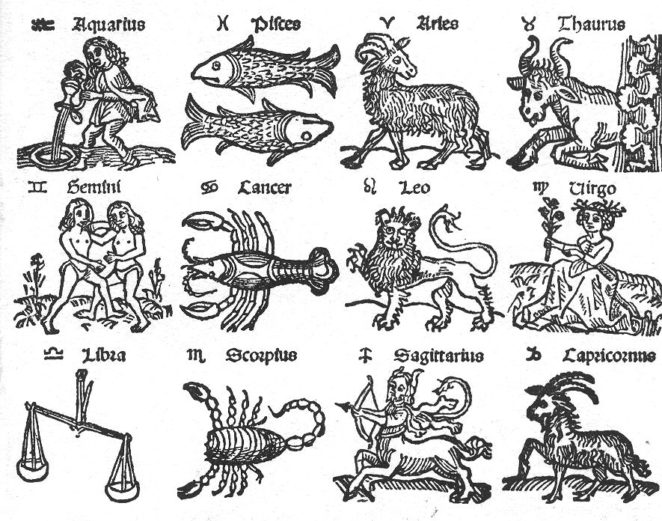

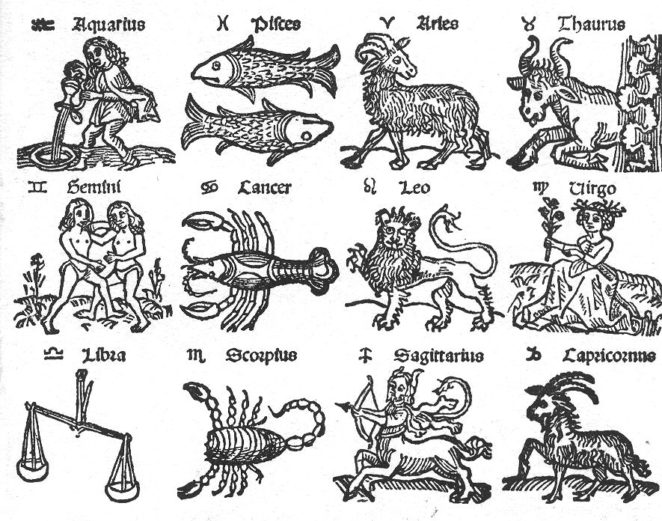

Zodiacal nonsense

Tuesday 27 March 2018

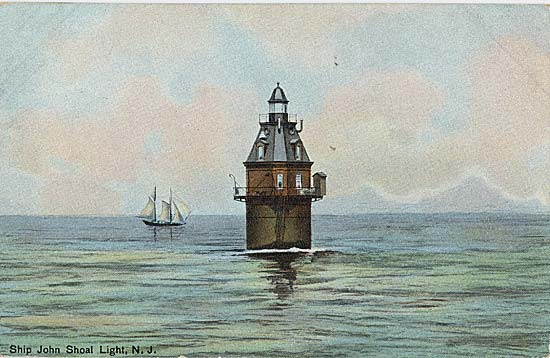

Two lighthouses - haunted or cursed

The Worm Charming World Championships

Monday 26 March 2018

The ring finger

The fourth finger (if the thumb counts as

the first!) is traditionally the finger on which engagement and wedding rings

are worn. But why is this?

It comes from an ancient (and entirely

erroneous) belief that a nerve runs from this finger directly to the heart.

Given that the heart has always been renowned as the seat of love – hence

“giving your heart” and having “heart-felt emotions” – the link to the rings

that signified love was appropriate enough.

This idea is also the reason why the finger

has been called the “medical finger”. The Greeks and Romans reckoned that the

nerve mentioned above would “warn the heart” if the finger came into contact

with anything noxious, so the finger was used to stir medical concoctions.

Presumably, if your heart jumped a beat during this process you would stop

stirring and re-constitute your mixture so that it would be less likely to kill

the patient!

Despite the complete lack of evidence for

this belief, some people still maintain the superstition that it is unlucky to

rub in ointment or scratch the skin with any finger other than the fourth.

© John Welford

Sunday 25 March 2018

The highest mountain is not the tallest

The ghost of Pawleys Island

Saturday 24 March 2018

The exception that proves the rule

Tuesday 20 March 2018

Not the Loch Ness Monster!

Saturday 17 March 2018

Don't fly your flag upside down!

Thursday 15 March 2018

Burning ears: an ancient superstition

The superstition – for it is nothing more than that – only applies when the talking is being done way out of earshot – it is not the case that you suspect that you are the subject of discussion between people on the other side of the room but can’t quite hear what they are saying.

It might surprise you to learn that this notion owes its existence to the Roman writer Pliny the Elder, who wrote during the first century AD and was a victim of the eruption of Vesuvius that buried Pompeii and Herculaneum in 79 AD. Pliny set out to write down as much knowledge – about everything – as he could gather, producing 37 volumes of his “Natural History”. It was his insatiable curiosity that prompted him to get too close to Vesuvius.

In Book 28 of Natural History Pliny wrote a collection of commonly held superstitions, and he managed to find and record around 20,000 of them. Somewhere on the list was:

“… it is believed that absent people divine, by the ringing in their ears, that people are talking about them.”

It is important to remember that Pliny’s intention was to debunk all these superstitions, not to publicize them, but the latter does appear to have been the end result.

One writer who took up the idea – whether directly or indirectly from Pliny is not known – was Geoffrey Chaucer, who used it in his Troilus and Criseyde, written in the 1370s. Criseyde’s uncle Pandarus tells her that he and Troilus will:

“… speak of thee somewhat … when thou art gone, to make thy ears glow”

This is not quite what Pliny had in mind, given that the person with glowing ears is not supposed to know that they are the topic of conversation, but only to assume that they are - due to the red ears!

Although this is clearly a piece of nonsense, as Pliny tried to make clear, the superstition is still around nearly 2,000 years later. However, let’s hope that not too many people take it seriously. It is almost always mentioned as a joke, such as: “We were talking about you yesterday, were your ears burning?” – to which the answer should always be “No”!